Prior to the invention of the compass, directions at sea were determined primarily by the position of celestial bodies. For thousands of years, navigators had found their way using the sun and the stars. In the northern hemisphere, seafarers would use Polaris – the North Star – to work out which direction was north in order to help them navigate across the seas. If they could see Polaris, they knew which way they were heading. While handy, this technique clearly has substantial limitations, as it is only of any use at night, with clear skies.

Divination Compasses

Naturally magnetized iron ore, or magnetite, also referred to as lodestone, seems to have been initially discovered in what is now modern China. If uninhibited by gravity and friction, this material was observed to orient itself to a north-south axis. During China’s Han Dynasty, between 300 and 200 BC, compasses were made but, ironically, not used for navigation - but rather for divination.

It is easy to imagine how the lodestone would have been seen as possessing magical properties, and hence early compasses functioned as tools of geomancy, used to foretell the future. The use of compasses was also important for feng shui, the art of establishing harmony in a room or building by aligning various features to the cardinal compass points.

Early Navigational Compasses

By the time of the Tang dynasty (7th century), Chinese scholars had devised a way to magnetize iron needles by rubbing them with magnetite. They had also observed that needles cooled from red heat and held in the north-south orientation would become magnetic. These more refined needle compasses could then be floated in water (wet compass), or placed upon a pointed shaft or suspended from a silk thread (dry compass). This portability made them much better suited to navigation purposes.

European mariners

By the 1300s, magnetic compasses began to appear across Europe and the Middle East. Although some historians contend that the Europeans independently created magnetic compasses from iron ore several centuries after the Chinese, most believe that the Chinese introduced their compass to the Muslims, who then shared this knowledge with Europeans.

In any case, the arrival of the compass was very significant for seafaring navigation, which, until that point, had relied on the sun or stars. The arrival of the compass allowed for maritime travel throughout the year, as opposed to being restricted to the fairer months.

Age of Discovery

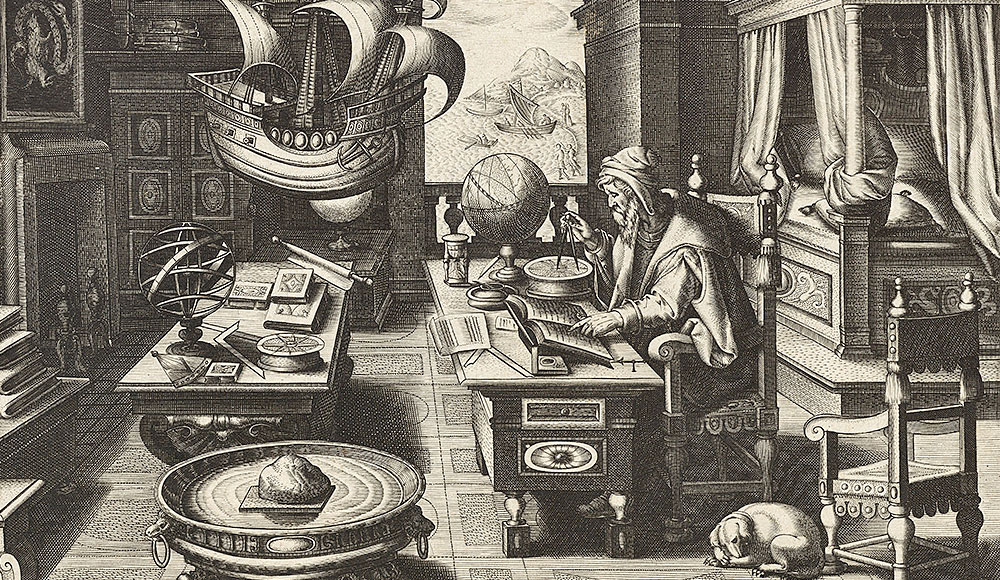

With a compass in hand, European mariners were better equipped to sail in the open seas, out of sight of land. The compass was a major contributor to the possibility of the Age of Discovery: a time of worldwide exploration on the part of Europeans that occurred roughly between the 15th and 18th centuries.

It was during this time that navigators and merchants charted sea routes to China, Japan and the Indonesian Islands, and established the trade of silk, tea and spices. It was also the time when Spanish conquistadors were encountering the Aztec and Inca civilizations of Central and South America and when explorers were learning of the wondrous natural resources of North America. The increase in sea travel and trade routes, enabled by the compass, led to European settlements in the Americas.

The Magnetic Crusade

By the 16th century, compasses and charts were indispensable tools for ships sailing at sea. But even then, navigators and sailors knew that there was something strange about their compasses. They could see Polaris, but noticed that their compasses didn’t always align with it: they didn’t always point north.

During the 15th Century, navigators began to understand that compass needles do not point directly to the North Pole but rather to some nearby point; in Europe, compass needles pointed slightly east of true north. To counteract this difficulty, British navigators adopted conventional meridional compasses, in which the north on the compass dial and the “needle north” were the same when the ship passed a certain point in Cornwall, England.

Scientists began to question what could be causing this variation, or as it became known, ‘magnetic declination’.

In the 1830s, British scientists initiated what became known as the Magnetic Crusade. This was an opportunity for Victorian scientists to travel around the world to measure magnetic deviation. The survey was to be used to aid ships and navigation, but it was also designed to better understand why the Earth’s magnetic field changes over time and space.

Technical Improvements

Over the centuries a number of technical improvements have been made in the magnetic compass. Many of these were pioneered by the British, whose large empire was kept together by naval power and who relied heavily upon navigational devices.

By the 13th century, the compass needle had been mounted upon a pin standing on the bottom of the compass bowl. At first only north and south were marked on the bowl, but then the other 30 principal points of direction that are familiar to us today were filled in.

The Compass Rose

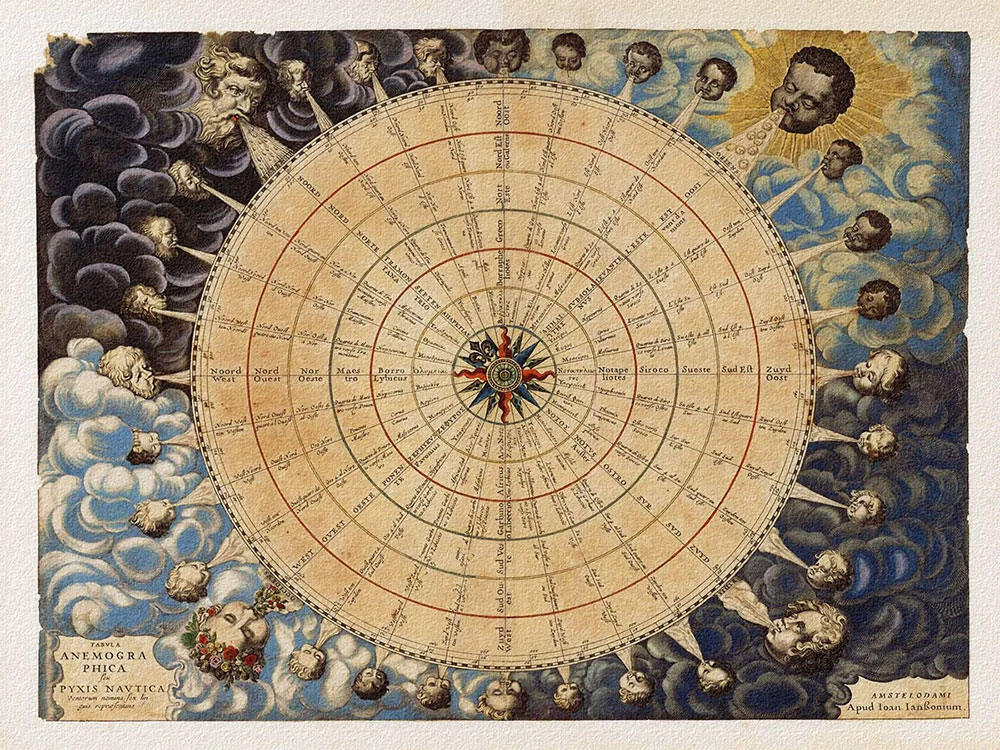

The 32 cardinal points were originally drawn to indicate winds, and were used by sailors in navigation. The 32 points represented the eight major winds, the eight half-winds, and the 16 quarter-winds. All 32 points, their degrees, and their names can be seen here.

On early compass roses, the eight major winds can be seen with a letter initial above the line marking its name, as we do with N (north), E (east), S (south), and W (west) today. Later compass roses, around the time of Portuguese exploration and Christopher Columbus, show a fleur-de-lys replacing the initial letter T (for tramontana, the name of the north wind) that marked north, and a cross replacing the initial letter L (for levante) that marked east, showing the direction of the Holy Land.

Flavio Gioja (fl. 1302), an Italian marine pilot, is often credited with perfecting the sailor's compass by suspending its needle over a fleur-de-lis design, which pointed north. He also enclosed the needle in a little box with a glass cover.

The Modern liquid-filled compass

Unlike dry compasses, which were easily disturbed by shocks and vibration, liquid-filled compasses were plagued by leaks and were difficult to repair. Neither, however, was decisively advantageous until 1862, when the first liquid compass was made with a system of bellows which expanded and contracted with the liquid, preventing most leaks. With these improvements liquid compasses made dry compasses obsolete by the end of the 19th century.

In 1936, Tuomas Vohlonen of Finland invented and patented the first successful portable liquid-filled compass designed for individual use.

The Dalvey Compass

Dalvey Compasses are recognised around the world: our brand synonymous with quality and integrity. We first launched the Dalvey Voyager Compass over 30 years ago, and have continued to innovate since then. The Voyager Compass is now a recognised design classic, crafted from high quality materials, to exacting standards: combining mirror-polished, precision-engineered stainless steel casing with exceptional detailing in the badge, bezel, and pommel, and a liquid-damped, quick-setting compass featuring a luxury-watch-standard dial. The latest Voyager Compasses feature mirror-polished interior case lids: the perfect canvas for personal inscriptions and injunctions to act a certain way: “Go confidently in the direction of your dreams”.

The Voyager Compass

Over time the range has expanded to include the Grand Voyager Compass: a larger, more presentational cousin of the Voyager, with a half-hunter-style window in the case lid and deep-engraved detailing in the window mount and case interior. The Presentation Grand Voyager features a beautiful, piano-lacquered box, and is especially well-suited to commemorating significant occasions such as christenings, graduations, weddings, anniversaries and retirements.

The Grand Voyager Presentation Set

The Voyager Expedition Flask combines our expertise in hip flasks with that in compasses, and is a truly beautiful object, guaranteed to become a dependable companion on trips and outdoor excursions. The stunning compass module and its deep-engraved bezel nest perfectly within the body of the flask: especially popular as a gift for groomsmen, or for 18th and 21st birthdays.

The Voyager Expedition Flask

Related articles:

The History of the Compass

How to use a compass Step-by-Step?

How does a compass work?